If I had £1 for every time I heard ‘I don’t get it!’, I could probably buy a new (modestly sized) car. That phrase is banned in my classroom. What does ‘get’ mean? What is ‘it’? Did you actually read the question?

And there we have it: reading the question.

Today’s little life skill strategy can work for all levels of literacy – because you don’t need any! I’ve taught a lot of students who just shut down when they see wordy questions and don’t look at the big picture – literally. There can be a really obvious diagram and they will skip the question. They just don’t try!

Now as you may be aware, I’m based in Wales in the UK. For those outside the UK, Wales is a principality within Great Britain. Although everyone speaks english, the traditional mother tongue is welsh – it’s particularly spoken in the North/West of the country. If you attend a welsh language school, you can do all your exams in welsh. A GCSE is called a TGAU.

But why am I telling you this?

Well, this means that the WJEC/CBAC exam board publishes their exam papers in welsh and english. Identical papers, different languages. I teach over the border in England, where only one or two students per year can speak welsh. This is where it gets interesting …

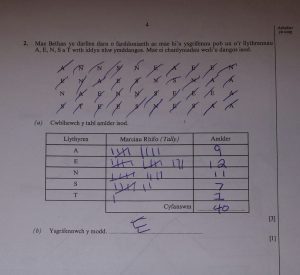

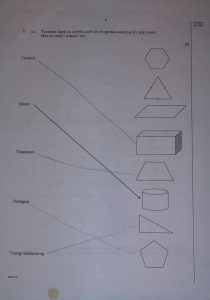

I went through a welsh language ‘Mathemateg’ paper and picked out the questions which involved diagrams – I also picked out the matching English questions so I was clear on the questions (not a native welsh speaker, just a learner). I gave my GCSE class the Welsh questions and told them to figure out what was going on. After the initial disbelief they had a really good go at the questions. Their comments included:

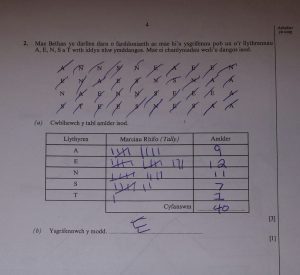

‘Well, it’s obvious it’s a tally chart’

‘Just fill in the table with the numbers from the pattern’

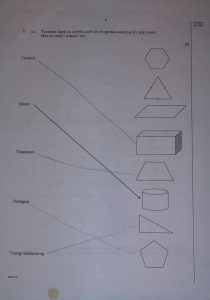

‘That’s got to be a special type of triangle’ (answer isn’t correct, but idea was)

‘Just use angles in a triangle to work it out’

I was impressed – they were constructively arguing about questions and covering diagrams in good maths. When we went over the questions they were telling me how easy it was, yet the week before they’d skipped questions like the angle problem in an assessment! I explained why I’d done it and told them they didn’t need to keep the worksheets as I’d made my point. I was stunned by the number of students who wanted to take them home to show their parents – they were proud of their problem solving – 16 year olds wanting to show off their Maths skills!

This idea can be used with any bilingual exam board or any language that you speak that the students don’t. It’s a good tool for getting over ‘question blindness ‘ and literacy confidence issues too.

These are the exam papers I used:

WJEC GCSE Maths

CBAC TGAU Mathemateg

If you look at the web addresses there is one digit difference to differentiate between the languages, meaning if you go on the WJEC english language website you can find the welsh equivalent by swapping a 0 for a 5 in the second to last digit.

Like this:

Like Loading...